THE EARLY YEARS

(1955-1957)

When I told my mother that I had decided to become a photographer the first question she asked me was “Yes, but what are you really going to do to earn a living?” And Dad followed up with: “You should take teaching. A teacher will always find a job, wherever you go. Then on weekends and during the summer you can be a photographer.”

Of course they had reasons to believe that. They had lived through the Great Depression and those people lucky enough to have worked for the government, like, say, teachers, postal workers, police officers and firemen, even the garbage men, continued to earn a living while others, like my father and his pals, they lost jobs and couldn’t find work. Another reason they had problems with me becoming a photographer: the only other photographers they had any contact with were either the sweaty guys who rudely careened through bar mitzvahs and weddings, snapping pictures and pushing revelers this way and that—or the mousy guy who once shot their mug shots, who had fumbled over his shutter cable checking the exposure, over and over again, even though he had shot the same picture, in the same place, with the same camera and same lens on the same film, using the same lighting for thirty years. You can see why I still get agita whenever I think about it.

The other unspoken reason for their concern was that they had no reason to believe I would succeed at making a living as any kind of photographer, and so, when I told them that I wanted to take pictures for magazines they really rolled their eyes. You see, I had a history of dreaming. Not that dreaming is a bad thing. And I mean, daydreaming. I believe you have a better chance for success if first spend some time dreaming of success. When my folks were buying a small piece of land on a lake in Ridgefield, Connecticut to build their summer home, I would lie in bed, before falling asleep, dreaming of the pirate ship I would build and sail out onto the lake. It would have a small cabin where I would sleep and the raised quarterdeck where I would sit and study the lakeshore ready to attack unsuspecting boaters. Those dreams were so real, I could smell them.

My desire to be a photographer was launched by Simon Nathan and his then wife, Ida Wyman, who had moved into my Bronx neighborhood and who had caused my interest in the camera to blossom. With each new bloom my parents felt they were losing the battle for my future. Mom would tell me which of the neighborhood kids was heading off to college to study teaching (my emphasis), or some real endeavor.

I had, a year earlier, entered the High School of Industrial Art in Manhattan, and having no desire to join the photography program offered there, studied what my brother Mel had studied, advertising design.

By graduation I thought I could not entertain even thinking about applying to a City or State college or university so I applied for admission to out-of-town schools, and my parents, delirious that I had given up the notion of becoming a photographer, agreed to foot the bill. Though my high school guidance counselor believed the whole application process a waste of time and would lead nowhere, he helped me find colleges where I might have some chance of being accepted.

I applied to Temple University (I liked the name), The University of Kentucky, far, but not too far, the University of Virginia, The University of Pennsylvania (my mother’s choice, it was a short train ride) and Ohio University (I was attracted to the course in television directing – a growing field). In mid-summer, after much anxious waiting and with my eyes peeled for the daily mail delivery, I finally received a letter congratulating me on my fine high school studies and with great expectations for a successful college career, I was accepted to Ohio U. Fine high school studies? Did they have the right guy? Nevertheless, when September rolled around, with some trepidation – and lacking a racoon fur overcoat, off I went by the Pennsylvania railway – to Athen, Ohio. Another world as far from the Bronx as Jupiter or Mars.

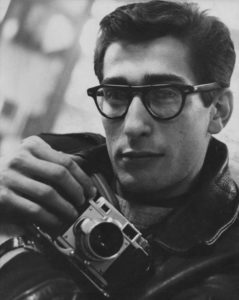

Photo Michael Amberger

I was, without knowing or understanding it, preparing myself for the profession I so deeply desired – photojournalism.

But, after two years, because of poor grades in my academic studies, I was asked to leave O.U. (temporarily) but not before discovering their wonderful photography department and not before making friends with men, and women who would one day be among the finest photojournalists of our time and friends who sustained me and my work for 45 years. Without having attended Ohio University, even for just two years, I could not have fulfilled my dreams.

That says a lot about that school and the Photo Department. But, there’s more to being a working photojournalist than education – one must be prepared to enter forbidden zones, one must never accept the words “No, you cannot.” That always had to be followed by one’s own words: “Watch me!”

Returning home to The Bronx I found various odd jobs as a laboratory assistant and printer in a baby photography “mill.” Great business, I was told. They’ll never run out of subjects. “Yeah,” I answered. “Maybe I should become a photographer at a funeral home. They have the same potential for endless subjects.”

“But they don’t make you smile,” my mom commented.

I took a job as a photographer for a personal injury attorney shooting pictures of accident scenes: broken curbs and stairs, ceiling that had collapsed on people, sidewalk fractures that caused falls and broken bones . My mom’s worst fears had suddenly become my life, a nightmare of miserable photography jobs and I had to do something about it.

(CONTINUED…)

Leave a Reply