SIXTY STRANGE DAYS

(October – December 1961)

It didn’t take much to convince Don Moser, or his bosses, at Life to invest in the Basic Training project. It wouldn’t cost them any money so they agreed to supply the film and to process it. I brought with me two Nikon SP rangefinder cameras with two lenses (105mm and 35mm) and a Sekonic incident light reading meter. I bought a small, rugged dark leather case to carry them and a dozen rolls of Tri-X film around.

On October 13th, I reported to 39 Whitehall Street as directed carrying the cameras and was certain somehow that they’d be stolen from me during my physical exam (they weren’t). I was immediately the target of some jokes, the first of many, and made it through the physical and “mental” exams was sworn in and ordered to the buses. I had enough time for a quick call to Mary who had been waiting by the phone to see if I would actually be inducted. When I told her she cried.

Our lives would be different for the next two years. Those heady days in The City, the long, hand-holding walks up Madison Avenue, The water fights at Paris Match, the excitement of late night assignations in friendly apartments, or babysitting for Slade’s kids out in Brooklyn, nights in New York, weekend parties with the Ohio U. crowd: Moser, Judy and John Ross, Pat and Paul Fusco, Nancy and Jim Dine. We wouldn’t get to watch an inebriated Donnie Pasternak telephone Ernest Hemingway in Havana trying as he might to convince Mary Hemingway that he was really, really a good friend of Papa H., that she should put Ernie on the phone (until one night Papa H. got on the phone – actually got on the other end of the phone – only to tell Donnie to “never call this number again.”

Both Mary Feder and I knew that there are defining turning points in life, forks in the road leading off in new directions, sometimes good, sometimes not so good. Both of us were thinking the same thing. What path were we on now? Where would this “Army thing” lead us? Would we be the same? Would our love endure this? I didn’t have much time to think deeply about these changes; I was the one going off into a new world, a world of trepidation and excitement. There’s hardly a man alive who cannot find the concept of shooting big guns and testing your mettle intriguing and stimulating.

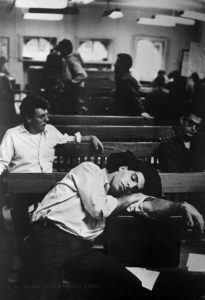

Whitehall Street Induction Center didn’t quite measure up to the intriguing notion and most certainly wasn’t stimulating except if you consider it only as a venue for shooting photographs. The nervousness of the new inductees was palpable. Out came the Nikon, and slowly but confidently I began my picture essay, my commentary in images that would later be a book titled: Sixty Strange Days. Before leaving Whitehall Street on the bus to “Hell” I shot a roll of film during the exams, respecting, of course, the privacy of the near naked inductees.

We arrived at Fort Dix, New Jersey sometime in the early evening but the sun was gone and the night was without any moon light. On the way out of Manhattan, many of the new recruits, the youngest ones, shouted from the open bus windows to any and all that they were heading for Berlin. Some actually shouted that they were on their way to Vee-et-Nam having recently read about the hostilities breaking in Southeast Asia, the name of the country involved and its capital city. “Saigon Express,” they shouted with little apparent fear oblivious to the horrible future awaiting some of them.

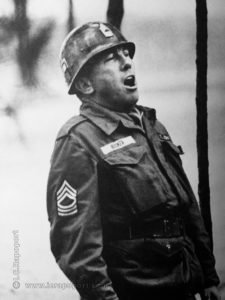

At Fort Dix, we sat in the bus as a new hush fell over us as we waited for the next “shoe to drop.” Suddenly the front and rear doors opened and two uniformed soldiers appeared one carrying an iron pipe that he banged on the overhead luggage racks walking the length of the bus and screaming for us to get off. All the recruits scrambled, grabbing their small overnighters and leaping from the stairs to the gravel roadway.

“I am the devil!” one of the cadre screamed at us. “Get your asses off’n this bus!”

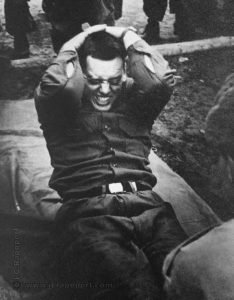

I stepped off the bus following the orders of the crazed cadre. The recruits stood in a line facing the bus. We were hazed, screamed at from three inches away. Some of us laughed in the faces of the silver-helmeted training sergeants who freaked out and demanded certain of the recruits drop to the ground and begin series of pushups but they refused to do it.

“Am I to understand that you refuse to follow a command?”

“That’s right,” the recruit answered.

“Well, son, you’ve just bought yourself eight weeks of hell,” the sergeant screamed then grabbed the recruit by the neck and forced him to the ground. “You start pushin’”

As dark as it was there was enough light for a slow-shutter exposure so I pulled my Nikon from its case and stepped out of line and shot a picture of the recruit on the ground with the sergeant standing over him. A second sergeant stepped up to me, his face turning purple with rage.

“Just that the fuck do you think you are doing?”

“Taking pictures, sir,” I answered.

“You think you are on a fucking vacation, soldier? You put that camera away and get the fuck back in the fucking line!”

I stepped back. There was no use arguing at this point. I would pick and choose my time and the kind of photographs I’d be missing here, in the parking lot of the Reception Center weren’t worth the energy. I had a letter in my camera bag, two letters in fact. One from Life magazine authorizing me to photograph my basic training for Life, which of course would mean nothing to these training noncoms, but the second letter was from Colonel Kline of OCINFO, in the Pentagon, stating that Private Rapoport had the permission and full cooperation of the Pentagon to photograph the basic training of his unit as long as it didn’t interfere with his or the company’s training exercises.

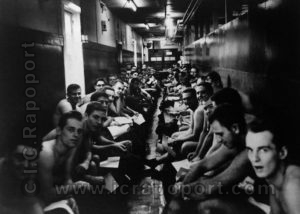

We were led en masse into the reception center incoming recruit billets, assigned bunks and told to form up outside in fifteen minutes to march to the mess hall.

After a meal and a restless night we were led to the reception center where we were given a duffel bag, had our name stenciled onto it, then complete new uniforms to fill the bag. Our heads were shaved, we had the necessary inoculation shots, back onto buses and we were driven to our training company barracks.

It was there that I was again, confronted by the training sergeants regarding my picture taking. I showed them the letters. They were not convinced but arranged for me to meet with the company commander.

Once in his office, standing at attention in front of him. “I’m sorry, sir, but this is all very new to me,” I replied when he told me I was to salute him when I came into the office and state my name. He was surprised at the letters, especially the one from the Pentagon.

“Who do you know?” he asked, genuinely concerned that my connections with the “higher-ups” was threatening to him.

“I met with the officers in OCINFO before my induction and they were impressed with my photography work,” I answered. “We discussed my photographing my training and they were quite interested in the possibilities it presented, being there’s such a big push for recruits, and such,” I went on.

The captain was equally impressed that his training company was chosen quite by accident to be the training company that would appear in LIFE magazine. He agreed to assist me in anyway he could and my first concern was the safety of my cameras. He said he’d be sure to have me assigned to one of the squad leader rooms off the main barracks where the doors could be locked. Of course, I’d have to be squad leader to get a bunk in there and I agreed to accept the responsibility. The captain told the training sergeants that my papers from the Pentagon were legitimate and that they should cooperate with me so that the photo-essay of our basic training cycle be seen in a good light.

The sergeants were ambivalent regarding my special situation. The resented the fact that I had special permissions from the highest brass in the Army and at the same time they were a bit star struck that they would be, in their minds, the center of attention in the picture story I was about to begin shooting.

As the weeks passed, my fellow recruits began to relax around me, and their own resentment, that I had a special, almost cushy job, seemed to dissipate. I made friends with most of the men, and the sergeants turned out to helpful and decent chaps. I like to take some credit for their congenial attitude towards all of us. Basic turned out to be informative and interesting. However, one thing the sergeants did say, if they had to go into combat with our company they’d go AWOL as they didn’t think we’d last ten minutes under fire.

He was wrong about that. Four years later, in Santo Domingo, while covering the insurrection there, I, Paul Slade and Arthur Schatz (of LIFE) came under fire and my days of basic training at For Dix came into play and I survived a few pretty scary situations thanks to the “Devil” training sergeant of Company P.

But for those days to have helped me I had to endure a certain amount of physical difficulty and mental harassment. To begin with, the training cadre of Papa Company weren’t the only ones unhappy with my “special circumstances.” My fellow inductees saw me as someone who was playing my cards and getting a sweet deal, sweeter than their own sometimes miserable Army existence. They were mostly right, of course. I had played my cards right and I did have a sweeter deal than most of the others. I have to say, the other squad leaders were also “chosen people,” those who shared the end bunk room with me (or with whom I shared their room).

What was unusual about this basic training company, the age differences of the recruits within each platoon. Because of the big call-up, I wasn’t the only 25 year old drafted. A good quarter of the company was men over the age of 23. The rest of the trainees were youngsters, eighteen or nineteen years old that had signed up, enlisted or volunteered for induction. So, we older types were sought out by the cadre to take leadership roles the most obvious, made squad leaders and assistant squad leaders. We were given black armbands with three or two stripes identifying us as temporary sergeants and corporals though those ranks were never uttered aloud by anyone.

My cameras survived the eight-week training cycle but I almost did not. Late in the training, just after Thanksgiving, I was stricken with pneumonia, double barreled pneumonia, and hospitalized in the base infirmary. Mary and my parents came down to visit me. I was in terrible shape for almost four days, unable to get out of bed to pee. Mary’s friend, Bea, was married to a young officer who had just completed his ROTC training and coincidentally assigned to a training company at Fort Dix. He was able to come in and visit me, though officers ‘socializing’ with enlisted men was mostly forbidden, especially if the enlisted man was a lowly trainee and not even considered a soldier yet.

The big fear was, of course, “recycling.” That’s what happens when trainees are so bad they cannot complete their training or learn nothing (a rare situation), or, the more common reason, sickness that makes a trainee miss out on certain important exercises or classes. I was missing out on them. But, my commanding officer knew that the Pentagon was waiting for me and let me back into the company to finish up my cycle.

One amusing moment came when a number of Jewish trainees (myself included) took the opportunity of the High Holiday Yom Kippur to be excused from that day’s training class, which happened to be the gas mask exercise. Because that part of our military education was mandatory, we would have to make up the class.

On a cold November morning, as the sun was rising, the entire company was formed up outside the barracks in full field gear. The First Sergeant stepped to the front of the formation and shouted out: “All Jewish personnel fall out for the gas chamber.”

There was a shocked silence then an immediate loud chorus of laughter. The sergeant was taken aback by the company’s reaction until he repeated the call out in his head and laughed, shaking his head. “You all know what I mean. Now go on, fall out, get your gas masks. Sergeant Booker will march you on over to November Company where you will join them at the gas…at the tear gas…place.”

In order for me to take pictures during our training it was agreed that I would always go first through whatever exercises the company had to experience. That way I could regroup, gather my cameras, and follow the troopers as they ran, crawled or climbed. With all eyes of the 240 men of Papa Company on me, I leaped, jumped, ducked and wallowed in rain or snow or sunshine. Sometimes eliciting praise, sometimes the instructing cadre would say, “Don’t do it the way he just did it.” Mostly though, nothing was said of my exemplary efforts.

As we neared the end of our training cycle, as the weather turned colder in mid-December, the recruits were starting to look like soldiers. In fact, having been given Korean War vintage weapons (M1s) and fatigues, we looked exactly like the soldiers who appeared in newsreels a nearly decade earlier. Certainly sitting in pouring freezing rain under soaking panchos and wet boots. It was no wonder that I caught the pneumonia bug. But with all that behind us, what had been an obstreperous collection of reluctant military trainees, dozens seemingly too old to have to listen to instructing sergeants, most of whom were career “short-timers,” noncoms mustering out of service after doing their 20 or 25 years. This was their last stop; the final notation on their long resumes of military postings. After having fought in WWII, then the Korean Conflict, after shepherding Airborne School advanced trainees to becoming Paratroopers and Rangers, after the responsibility of Squad Leader and Platoon Sergeant in combat conditions, after receiving their Combat Infantry Badge, Purple Hearts, Bronze Stars, here they were, babysitting a bunch of crybabies with Masters Degrees. Papa Company was loaded with regular guys from the financial world, publishing, college instructors (my best friend, John Medici, was a 24-year-old English teacher), there were cops and firefighters with three or four years experience. This was a group that didn’t take to being shouted at or threatened. This was a group who laughed at the sometimes ridiculous circumstances they found themselves in and laughed at the tantrums of the frustrated training sergeants who after four or five weeks, gave up trying to bend us into soldiers and laughed with us. Again, informing us that we were the absolute LAST collection of deadbeats they would lead into combat. That their safety in wartime could never be guaranteed by the men of Papa Company. And, they were probably right.

By the graduation ceremony, on the 16th of December, 1961, to the surprise of the officers, noncoms and most of all, the collection of military misfits, the so-called “deadbeats” of Papa Company marched with pride of accomplishment, off to the rest of their tour of duty. I would be given the MOS (Military Occupation Specialty) 841/photographer, and assigned to HQ Company, Fort Lee, Virginia. I was to report to the Public Information Office. Not the Pentagon.