THANKS TO CAPTAIN GALVÃO and THANKS TO RICHARD STEEDMAN

Part One (January, 1961)

What I didn’t get in the way of usable photographs from my few days on the cold Atlantic were more than made up for in my next assignment for Paris Match. To make this clear, though I wasn’t left with even one photo about a major story that followed closely after the Texas Tower disaster— namely, the audacious hijacking at sea of the ocean cruise ship Santa Maria — instead, I met the love of my life on the warm beaches of San Juan.

Glad not to have caught pneumonia on the frigid, icy decks of USS Sunbird, I tried warming up at home by sitting close to the radiators and staring comfortably from my sixth floor window at the snow flurries covering the Bronx, and of course, waiting for the phone to ring. When it did, I was surprised and delighted to hear Stephane Groueff wanting me to fly down to San Juan, Puerto Rico, immediately, to cover a breaking story. Puerto Rico! In January! What could be better? I was no stranger to San Juan. Having lived in San Juan in the fall of 1958 – while shooting the Father Landry photos for Jubilee magazine – and again in ’59, I still had friends and acquaintances living among the palms and Bougainvillea.

There were a number of flights from New York’s Idlewild Airport (yet to be named JFK) to San Juan each day but time was of the essence and the magazine booked me on the overnight flight; a DC-6 prop-jet, that flew seven hours from midnight to 8 A.M. (P.R. time). That particular Caribe Air flight, known to many travelers as the Vomit Comet, cost $59 one-way, and was the least expensive of the daily flights to the island. Once on board, I settled down near the rear of the aircraft and immediately found myself seated among a dozen other journalists, every one of them heading south to cover the big news story of the week: The hijacking of the cruise liner Santa Maria.

Days before, the world learned of this daring terrorist act on the high seas. Apparently, a Portuguese Naval Captain named Henriques Galvão, a political foe of Portugal’s strongman Salazar, along with an assortment of Spanish and Portuguese leftists, boarded the cruise liner in Venezuela as third class passengers. Once at sea, firing automatic weapons smuggled aboard in their luggage, the group took command of the bridge, and ultimately the entire vessel. A junior officer was killed and several others were wounded and they forced the ship’s captain to sail to Africa. By the time I was called to move on it, the hijacking was already big news, but the cruise ship had disappeared on azure waters of the Caribbean and had eluded a massive air/sea search by the United States Naval aircraft based out of San Juan’s US Naval Air Station.

What I recalled most about the flight were that the dozen or so journalists, photographers, and television camera crews filling the seats at the rear of the prop plane, did not sleep for most of the flight. But they did drink. They were loud and raucous and they initiated me into their ink and picture corps once I told them I was heading down to San Juan on the same story for Paris Match magazine. Journalists have one thing in common for sure; they love to tell stories. They love to reminisce about assignments of old, when life was good, or hard, or fun, or miserable or scary. As a young photojournalist I was left out of the conversations until I mentioned that I was out at the Texas Tower disaster. This peaked the interests of my nearby seat mates who hadn’t made the cold and miserably wet voyage out to the sunken radar tower. I regaled them with our suspicions that there were civilian divers trapped in a recompression chamber on the bottom of the Atlantic and that the Navy brass, or rather, the Captain of the USS Sunbird was too concerned with losing his own “frogmen” in a failed attempted rescue.

It wasn’t long before they became bored with their stories, and mine, and began to drink earnestly, and since drinking and making passes at the stewardesses was the play of the day, screaming and laughing loudly was the accompanying sound track. I have to admit I was not an innocent and I tried proving that my recent admission into this exclusive club was no fluke and I was the equal of the experienced, crusty old-timers.

Things began to get out of hand in mid-flight, about the time when most of the other eighty passengers wanted to sleep. At last, one intrepid man who was closest to the press mob stood up and demanded quiet. He shouted something like: “Do you realize some of us want to sleep and don’t find your jokes as funny as you do?” Well, the press mob went quiet immediately. That is until one of them dipped a paper napkin into his drink and threw the wet gob at the complainer. It stuck for a moment, leaving a stain on the man’s shirt. He called the spitballer “infantile,” and in fact accused all of us, who were doubled over drunk and laughing, as being infantile. When he sat back down he was bombarded with half-dozen more alcohol-drenched monster spitballs. Wiping his head, he stormed to the front of the plane to complain to the stewardesses, and the pilot, about our behavior—or to go to the lavatory. We didn’t know which. In any case, one of the television camera technicians leapt to his feet, opened the overhead bin, and grabbing his tool bag, set to work removing the bolts that held the complainer’s chair. It took only a minute or two as the crowd laughed and hooted, the chair was lifted up and passed back over the heads of the rowdy press gang and thrown into an empty lavatory in the rear of the aircraft. Returning from the toilet (or the unresponsive flight crew), the complainer looked down at the empty void that had once been occupied by his seat. The press gang sat silently, stifling their laughter, until the complainer’s seat mate pointed to the rear of the plane. In due time, of course, with some prodding by the flight attendants, the seat was airlifted overhead to its rightful spot and bolted back into place. The complainer plopped down and eventually went to sleep. As did all the rest of us.

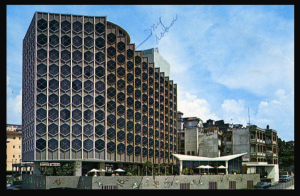

Early morning arrival at San Juan Airport we all were to discover what we had most feared. It being the third week of January, height of the tourist season in Puerto Rico, hotel rooms were impossible to find. The crowd of hung-over journalists called futilely from the bank of pay phones in the airport’s arrival lobby. Having lived in P.R. with my friend Mickey Amberger, a few years earlier, I had a short list of contacts with whom I might impose upon to let me sleep on a couch or floors, or they might even have a room for me. One old pal was the son of the owner of the beautifully landscaped Villa Firenze, an Italian restaurant/inn. Serge’s villa was fully booked but he tipped me off about the Miramar Charterhouse, a brand new hotel by the bridge, not far from the Caribe Hilton, that was completing construction. He suggested I call the manager, a drinking pal of his. I did, and I was able to persuade him to rent more than dozen rooms that were almost completed. He warned that there was still dust and we’d have to share the elevators with construction workers, and that there’d be noise all day. He said several of the upper floors had working plumbing and beds, though he was still in the process of training the housekeeping staff. He could let us have a few dozen rooms for $15 dollars a night. And that was $6 dollars less than rooms at the Caribe Hilton! When I relayed this information to the frustrated group of journalists they were ecstatic and if they could, would have lifted me upon their shoulders and carried me to the taxi stand.

The Miramar Hotel manager was harried as the nearly twenty members of the press corps arrived and dropped their enormous load of luggage and equipment onto the polished stone floors of the hotel lobby crisscrossed with paper ‘carpeting’. The Miramar was unique in that it had octagonal shaped, floor-to-ceiling, windows offering incredible views of the inlet and the sea. Most of us were sent up to the 12th floor. The elevators were padded with protective curtains. Plaster powder and chips and covered everything. As we each sought our rooms, dodging housekeepers and their carts, busy making up the brand new beds. Plastic bagging lined the corridors. My room was at the very end of the hall and it was pretty nice for a half-appointed room that was missing a chair. Once inside, I could look out of the floor-to-ceiling, octagonal windows overlooking Old San Juan. The view was spectacular. I threw my B-4 suitcase and camera cases onto the newly made bed and walked over to the window. At 8:30 in the morning the air was still and yet, it seemed I could almost smell the Jasmine. Staring out at the inlet and San Juan beyond, I looked down at the gardens that were still being worked on. Leaning close to the glass, if only to rest my forehead on it, my stomach dropped and heart stopped as well: THERE WAS NO GLASS! I fell backwards into the room. No glass in this window! I could have fallen twelve stories! At that very moment the room door opened and several workmen carefully angled a new window glass through the door frame. Letting them pass, I backed out into the corridor to warn the others. Several answered my shouts and met me in the hallway. Upon inspection they all had glass in their windows. The workmen told me in broken English that the original glass hadn’t fit properly and they removed it the night before to trim it. I picked up my gear and went down to the front desk. The manager went deathly white when he checked out my complaint and immediately moved me to a room on the 11th floor, a room that had a window with glass in it.

While waiting for word from the U.S. Navy I called an old friend, Richard Steedman, a photographer then working for the San Juan Star, the English language daily newspaper. Dick and I had lived in the same apartment building in the Bronx while he attended university classes. He had owned a Norton 99 Dominator motorcycle and introduced me to his fellow bike enthusiasts who hovered over and worked on their machines in a garage on Broadway and 177th Street, just across The Little Washington Bridge, the bridge that connected our Bronx neighborhood to Washington Heights in Manhattan. It was our friendship, and his interest in my photography, that provoked him to drop his engineering career studies and become a roving photojournalist like me. Dick eventually went on, in later years, to create the superior stock picture agency, The Stock Market, and became a multi-millionaire when he sold it to Corbis Images.

What he didn’t get, was Mary Joan Feder.

[x_blockquote type=”center”]This is Part One in a Series. Subscribe below to be notified of new posts. [/x_blockquote]

Leave a Reply