ABERFAN

The Days After

(Part Three)

The nightmares began a few weeks into my assignment. I had spent the first ten or twelve days immersed in the “story” I was about to tell with my photographs. As a photojournalist, my task was not merely to wander the village looking for striking images, though I did plenty of that, but to formulate a point of view. What story was I trying to tell? Was it “A Town Without Children”? Slowly I began to understand the story that needed to be told. It was about a village trying to return to normal after an unspeakable and unfathomable disastrous act of nature gone wild. And I was dealing with an angry village that shifted from weeping to shaking its fists. Sure nature went wild, but most believed that it needn’t have. There were early signs and the villagers felt betrayed. Somethings I could not capture with my cameras. There were places I could not enter to witness the incredible rage that boiled in the hearts of these rugged working class people.

One night, in my cold garret bed, I awoke sweating. I was sick. I had come down with something. But I also was awakened by a dream – my little boy, only 5 months old and seemingly safe in Manhattan with Mary, his mom, was covered in mud that swirled around him and I couldn’t reach him to pull him out and he was consumed by the slurry. I thought it was a sign and wanted to call home but that in itself was a near impossible task. Not at four in the morning. Not from the Mackintosh. The nightmare repeated itself even after I finally spoke to Mary on the phone and she assured me Benjamin was fine.

I looked forward to Jim Hick’s return from London. He’d come to pick up his interviews and we’d discuss the story. He’d bring me fresh film and take back to London my exposed film to be sent to the Life photo lab in New York.

I depended on Jim for comfort and assurances and he told me that the editors were very pleased with what they were seeing. He also brought me contact sheets of the film that was already processed so I could see what I had shot. The story was beginning to take shape. Jim and I eventually were asked by the Mine Managers if we wanted to experience what it was like to be a mile down below ground. They dressed us in coveralls, gave us helmets and headlamps, then took us down in the lift, way down. Far down. In the galleries below, the larger ‘rooms’ that had been cut and chiseled out of the rock, earth and coal seams, there was some light, but as we walked through the tunnels to where the miners were actually digging out the coal by hand, the only light we had were the beams of our headlamps.

Much of my time was spend wandering the village looking to find photographs that would “speak” to the story at hand. On one such walk, along sidewalks on Nixonville. It was there a striking photograph presented itself. A woman, in her housedress, stood in in her doorway watching as the children were returning home from the nearby temporary school. I photograph her and luckily also captured her son plodding along, heading home. I spoke to her. Her name was Sheila Lewis and she lost a daughter in the disaster. She welcomed me inside to tell me her story.

On one of Jim Hicks returns to Aberfan from London (he came several times and stayed a few nights) I tipped him off about a boy who had survived the disaster in his school room. He was the son of Llew Milk who had a small farm on the outskirts of Aberfan just north of the road to Merthyr Tydfil. The boy’s name was David Davies, perhaps the most common Welsh name after David Jones. Jim and I drove over to visit Ynysygored Farm and met with Llewellyn Davies and his family.

Llew Davies (Llew pronounced like Slew without the ‘S’ – try it) told us how he had rushed from the farm to the school when he heard what had happened and was struck immediately by the frantic digging of miners, parents, firemen and others. He saw a row of muck-covered children’s bodies just as the emergency workers were draping them with bedsheets and covers supplied by nearby families. Llew joined the rescue attempt, stepping into the bucket brigade – a line of men and women passing empty pails to the diggers in the chaos and handing back out, pails filled with mud and rock. A primitive but necessary method considering that heavy earth moving equipment could not be utilized because the vibrations might cause more damage inside the school rooms and also because immediate silence was called for, time and again, as sounds of another child alive was heard beneath the dirt and brick. The small bodies were carried up and passed out on the same bucket brigade line with shouts of “Another coming up.” Llew took this one and carried it to the nearby Nurse who was attending to the line of bodies. When she poured water over the boy’s face, Llew realized he was holding the body of his own son, David. The Nurse placed the 9 year down on the row, when she shouted: “This one’s alive!”

Yes, David was alive and they lifted him into an ambulance and drove immediately to Hospital.”It was a miracle,” Llewellyn told us. “Not one other child from David’s classroom survived. And no ones knows why.”

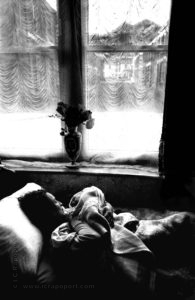

I found young David in his bedroom. He had been looking out his window and when he turned I took the first of many photographs of him.

David had no recollection of the event. To this day. David doesn’t recall much at all. At the time I photographed him, in the fields behind his home, he showed me the way he walked to school – along a dirt track that ran alongside a stream that was then filled with slurry and muck. Nearer to where the school once stood, the track had been obliterated by the avalanche.

I began making lists of photographs that were needed to complete the essay. The first child born in Aberfan after the disaster. The first wedding. Simple signs of new life, or normality, islands in a turbulent ocean of grief and helplessness. I asked around and was told that a family not far from the Mack was expecting a child any day. I went to visit them to get permission to photograph the birth (I had already photographed my own child’s birth and filmed and photographed two other births of friends’ children). The mother-to-be was reluctant to have a stranger with a camera there in the room but agreed to let me be nearby and enter immediately afterwards. I asked where she would deliver and they took me to the front parlor, the room on the street. And I could not believe my eyes. Opposite the home was a perpendicular street Any other home on the street would have had buildings across the way blocking the view beyond the village, but their house had this street and the opening provided us a view of the dreaded tips. She would have the baby on a cot, under the window, and outside we could see she was in the shadow of the tips.

With the first child out of the way I now moved to find the first wedding and within a week, I heard there was a bride from Aberfan about to be married by the Reverend Hughes – a hero of the tragedy – the man who assumed command initially of the rescue operation when it was a chaotic mess of individuals digging and clawing to find the windows and doors into the muck covered school building. I sought out the family to gain permission to photograph the wedding.

For weeks and weeks the children of the primary school, those who survived the horrendous events of the 21st of October, stayed home, close to their parents and neighbors.

Eventually, a location in the Conservative Club was arranged for the Pantglas surviving children to attend some classes and try to return life to some semblance of normal comings and going. I gathered the group of survivors and photographed them, having found the closing photograph to my photo essay on Aberfan: The Days After.

-end-

Leave a Reply