ABERFAN

The Days After

(Part Two)

The Mackintosh Pub became my friend. My only friend. As a journalist, I was an outcast and in some cases a despised one. Thanks to the hundreds of newspaper and TV reporters who came through Aberfan before me, a very bad taste was left in the mouths of the village residents.

When the last of the news reporters left the villagers breathed a sigh of relief and went to tending to their recovery, a massive undertaking. Imagine a small town, if one child is killed, how family, neighbors and friends would rally to that grieving family. A whole network of support would be formed – and from those ranks, many strong individuals, their wits about them, their emotions in check, would step up. Would be there. Now imagine a whole village racked with grief – when neighbors and friends would be suffering alongside in their own mournful world. This is what I encountered. Now, mind you, I’m not complaining so much considering what Aberfan had to deal with, but I had my own form of grief – I too was touched by their tragedies and I will tell you how and why.

It was the “one-on-ones” that got to me; when someone would find themselves alone with me, most likely at a table in the Mack pub. After some small talk, asking about my life, where I came from and did I have a family, etc., they would eventually bring up how the disaster impacted on their lives. I didn’t have to ask too many questions. They would let something seep out, like where they were when they heard about the disaster and what they did. Hardly anyone referred to the event as an “accident.” All were in lock step regarding the National Coal Board’s negligence. All would tell me how it was well known there was a leaky spring under the base of the tips. “You could see it plain as the nose on your face, Chuck. Sometimes gushing out, after a particularly hard rain.”

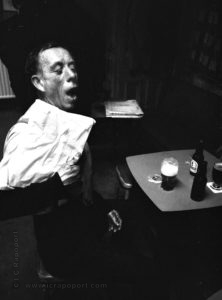

From benign recollections of the tips and the mines and the tragedy, the mood would change and become more somber, quieter, their eyes would moisten. Now I needn’t tell you these were for the most part miners. Rugged men who prided themselves on their rugged lives, their dangerous lives. Digging a mile below ground, sweating in pitch darkness with only headlamps to illuminate their work. Weeping is something they did not feel comfortably doing and so they would let their tears flow down their cheeks, wiping them away with a strong meaty hand, as they began to speak of the horrors of going home now to their families smaller by one, or sometimes two, children.

Their behavior spoke volumes. The more they drank their pints, the freer they became to demonstrate their grief.

There was no therapeutic means for these men to recover. I became the focus. I was the stranger, the outsider, the person they could share their feelings, exposing themselves, not fearing I would betray their trust. But in the end I was the one receiving these sad feelings and when the men stood up and went home at closing time, I was left holding their emotions.

I had selfish reasons for sitting and talking with these grieving individuals; I was making inroads to gain the trust and acceptance of these people. Without that, I couldn’t take the kinds of photographs I needed to take. I never thought I’d become their therapists. The best thing that resulted from my “sessions” with my new friends was my ability to begin moving around in their world, without suspicion and anger.

However, there was one incident worth noting. It was on a weekend afternoon in the Mack. The pub was crowded with miners and citizens of both Aberfan and Merthyr Vale and some from other outline villages. I was drinking at the bar, having a Woodpecker Cider, when one of my young miner friends came up to me – at the same time Stanley the Publican, behind the bar, moved closer to us.

“Chuck,” the young man cautioned me. “It be best that you leave the pub for now.” I turned and looked at him. What was the problem, I asked. “It’s Dai George. He’s over at the window table and he’s had a few too many and he’s been asking about you. He want to pound you, he says. Beat you good.” I looked at the window and saw the man staring at me. Only ten minutes earlier, I had taken his picture glaring my way.

My first reaction was one of disbelief. Could this really be happening? Did one of the men in the pub threaten to beat me up and now I’m being asked to leave, run out, chased from “my home” in the village. I thought quickly and decided that if I left, if I turned tail, it would just be worse for me. I decided to stay and “confront” this Dai George from Merthyr. Stanley grabbed my arm and gave me some background on Dai. “He’s the toughest bloke in the valley, Chuck. Everyone here agrees. No one has ever gone against him and won and now no one ever does. When the “Carny” comes to the valley the boxing man offers 10 quid to anyone who will go two minutes with his fighter and Dai’s knocked that bloke out several times that the fighter won’t even fight him anymore.”

So there. That was what I would be confronting. Well, I had no idea to fight Dai George, even before I was informed he was the toughest bloke in the valley, in all of South Wales for all I knew. Now, I’d have to use diplomacy to end the situation. So I asked what he was drinking, what the table was drinking, and bought a pitcher and carried it over to Dai George’s table and set it down.

“Take your pitcher elsewhere,” he ordered. “It’s not welcome here.” I raised my camera and took his picture and he sort of smiled, but it wasn’t the kind of smile that made me relax. “Look, Mr. George, I heard you want me out of the pub, which is where I am living…” He interrupted me at this point I am recalling and told me to move out of the village – that would be better for everyone. You “Journies” have done enough here. You’ve pissed on these people and aggravated their sadness…”

“I’m not a journalist. Not like the others,” I explained. “I’m not here reporting the news.” He wanted to know then what I was. What else can a man with a camera be sticking it in the faces of those grieving for their kiddies. “I’m a poet with a camera,” I said. The explanation popped into my head. I’m here using my camera to tell a story about this village and how the disaster…” Again he interrupted with a bigger grin. “A poet, he says?” Dai George announced to the whole room, A room that was quiet by now, waiting to see what would happen. “You’re in the land of poets. You know that? What do you know of poets?”

It was fortunate that one of the things I did learn when I was at Ohio U. was some of the poetry of Dylan Thomas from Swansea, not that far from Aberfan, on the shore. “I know Dylan Thomas,” I said. “Do ya?” He answered. “Let’s hear it then.” I reached back deep into my college memories, of reciting Thomas in the Student Union and began: “Now as I was young and easy under the apple boughs – About the lilting house and happy as the grass was green…”

ANOTHER VOICE chimed in from somewhere near the bar, joining me. “The night above the dingle starry – Time let me climb [sic] Golden in the heyday of his eye…” Everyone then laughed and the mood was broken. There were some applause; the man took his bow.

[x_blockquote type=”center”]This is Part Two in a Series. Subscribe below to be notified of new posts. [/x_blockquote]

Leave a Reply